Part of Series

Transforms

Brisbane, Australia.Details

| Part of | Seeing Sound |

| Where | State Library of Queensland |

| Date | Tuesday, 21 August 2007 |

Formal experimentation with sound and image relations is one key way that avant-garde filmmakers have challenged the ‘classical’ cinema. Some well-known film artists (famously Stan Brakhage) choose to eschew the ‘grand opera’ of sound altogether. Others have worked to problematise and question the way in which sound operates in moving images. These three films each subvert the conventional role and function of sound; to reinforce what we see in the image. Rather, they explore the ‘transformative’ potential of sound to radically alter the meaning of images.

Pip Chodorov’s Charlemagne 2: Piltzer uses the sound of piano playing as the structuring device for the entire film – matching the visual montage to the complex polyrhythms of the sound. To mirror the harmonic vibrancy and indeterminacy of Charlemagne Palestine’s music, Chodorov has optically printed every film frame in different combinations of colour, resulting in a kaleidoscopic visual music experience.

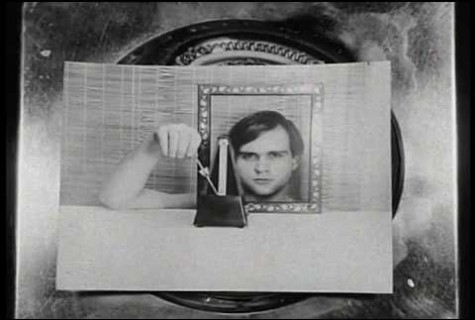

In Hollis Frampton’s Nostalgia a voiceover (the filmmaker Michael Snow) tells lucid stories as a series of photographic images slowly disintegrate on a hot stove. However, the narrator’s always describes the image that we have already watched burn. The spectator is forced to return to the memory of the image destroyed. Through this simple technique, Frampton, one of the great exponents of Structural cinema, reconfigures the authoritative ‘voice of god’ functions of the voiceover in narrative film and draws attention to its often pervasive role in structuring our understanding of films.

The Acousmêtre (a disembodied voice that seems to come from everywhere and therefore to have no clearly definded limits to its power) is also the ‘subject’ of John Smith’s Girl Chewing Gum. A half-shouting hidden voice calls attempts to control all it surveys through the ‘eye’ of a camera on a busy street. Firmly in the British tradition of absurdist humour, Smith’s film can be seen as wryly poking fun, not just at the stereotype of the megalomaniac director, but also the seriousness of fellow 1970s experimental filmmakers.

The films in the Trans-Forms program help us refresh our audio-visual perception of cinema. No longer just a ‘backing track’, sound takes centre stage in these films which transform our normal understanding of space, time and meaning.